By Sherry Sereboff

“Mister, will you get me out please?”

First responder Don Nelson was struck by the 10-year-old’s composure. The boy’s leg was broken and bent. He lay atop a heap of rubble and surviving classmates, sheltered under a fallen bookcase. Rescued within moments of the deadliest school disaster in American history, these fifth graders were lucky exceptions.

As New London’s longest night proceeded, most of the remaining children were found either dead or gravely injured.

In 1937, while the country at large suffered in the throes of the Great Depression, the small East Texas hamlet of New London enjoyed a prosperous respite. The 1930 success of wildcatter Dad Joiner’s Daisy Bradford Number 3 initiated the discovery of the largest known oil field in the world.

Formerly known as London, Texas, the community became New London in 1931 when it established a new post office and found that a London post office was already established elsewhere. The new post office, and the town as a result, was rechristened New London — some businesses retained the London name.

Situated in the heart of the “Great Black Giant,” New London became the richest rural school district in the nation. The influx of oil field workers and their families necessitated a larger school. Oil money fueled its construction.

Built in 1931, with additions in 1934, the combined junior-senior high school hosted the fifth through 11th grades and was the centerpiece of a new one million dollar campus. The school included a distinguished library and state-of-the-art laboratories. School grounds teemed with oil well jacks and the Wildcats played in the first lighted high school football field in Texas.

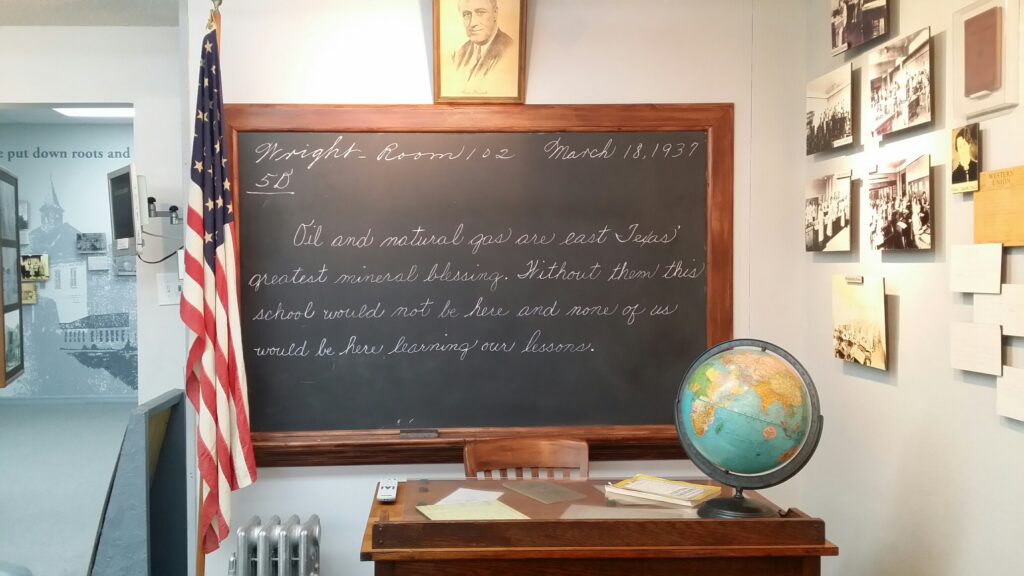

On Thursday, March 18, 1937, a cold and wet winter yielded to a beautiful spring afternoon. Excitement was in the air. Several of New London’s students prepared to compete in the Interscholastic League competitions in Henderson the next day. The district expected a stellar performance. New London teachers were exceptionally trained and highly paid; one of them wrote a reminder of the source of their good fortune on her blackboard:

“Oil and natural gas are East Texas’ greatest mineral blessings. Without them this school would not be here and none of us would be here learning our lessons.”

New London’s grateful citizens never anticipated petroleum’s bounty —- or its cost.

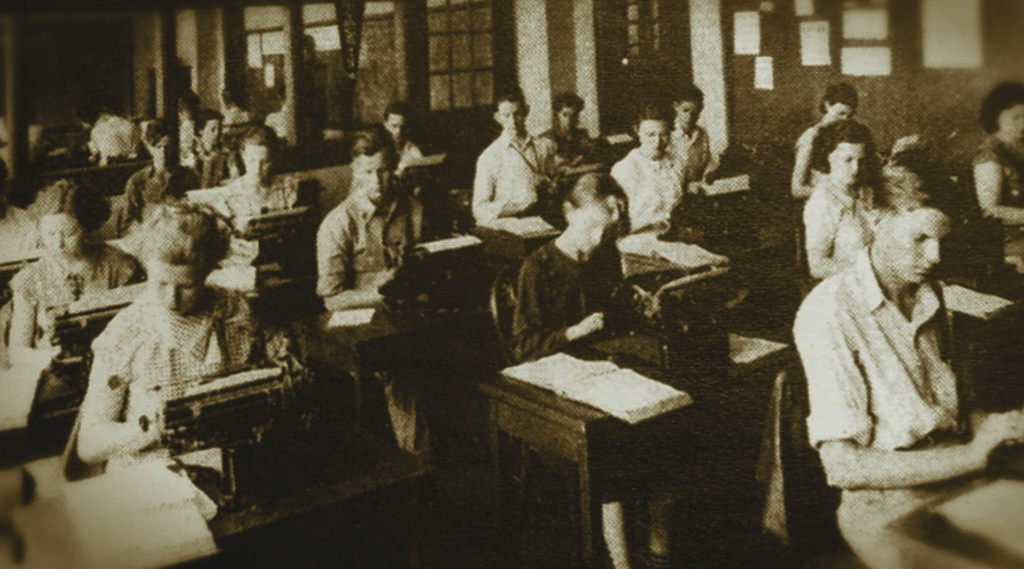

Students and staff looked forward to the three-day weekend ahead. Junior high and high school students were restless and giddy. In the gymnasium, mothers watched their elementary students perform a Mexican dance recital.

Just before school let out, at 3:17 p.m., shop teacher Lemmy Butler flipped the switch on a sander. A deafening boom stopped time on the wristwatches of New London’s future.

Witnesses agree that the 253-foot-long school lifted several feet off the ground before crashing back down in a mass of broken concrete, twisted steel, and collapsed bricks. The massive explosion shook buildings and rattled windows 10 miles away in Kilgore. Hundreds of children and their teachers lay buried beneath the rubble.

Mothers swarmed out of the gymnasium. They ran to the wreckage and frantically searched for their children through the thick plume of smoke and concrete dust.

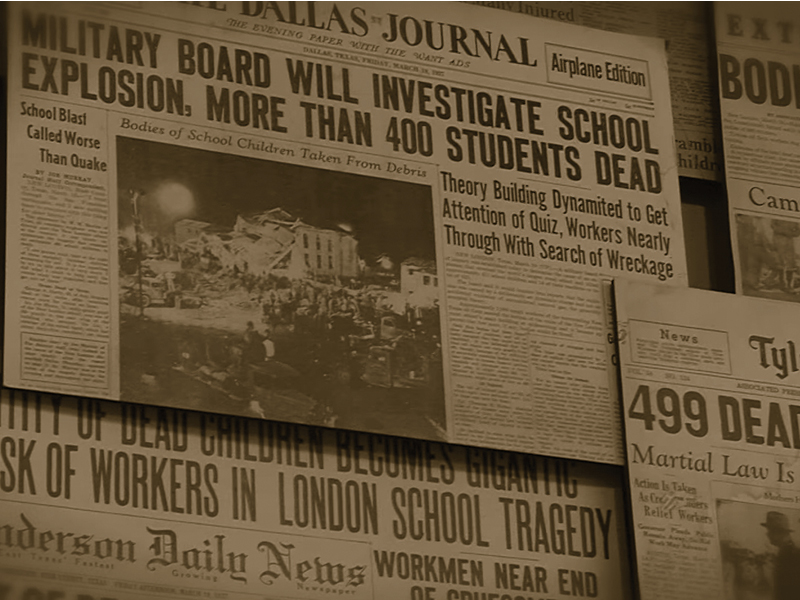

Pleas for help went out and volunteers streamed in. Descriptions of the disaster reached news desks within minutes. Twenty-year-old reporter Walter Cronkite was finishing his work day at the United Press International office in Dallas when the teletype machine tapped out a frantic message relaying word of the explosion. He grabbed his fedora and raced to East Texas to cover the unfolding tragedy.

Local Boy Scouts were first on the scene. They directed traffic as 1,500 oil-field workers rushed to the site and began digging with bare hands. Oil companies sent in winchers and acetylene torches. Governor James Allred declared martial law, calling in the Texas Rangers and the Texas National Guard.

Rescuers commandeered hundreds of peach baskets from a passing truck. While some men dug, others formed human brigades. Hundreds of hands passed debris and body parts in peach baskets to the school perimeter for the next 17 hours.

The American Legion and Salvation Army scrambled into action. The Red Cross set up supply stations. They provided coffee and gloves as a steady downpour ensued. Floodlights allowed the heroic volunteers to labor through the darkness and the rain.

As deceased children were removed from the wreckage, they were laid and covered near the fence. Throngs of mothers clung to the fence from the outside. They made no sound as the dead children were positioned on the grass, but when a live child was carried out, they embraced each other and cheered through tears.

Survivors were taken to 14 hospitals in the region. Doctors and nurses arrived from across Texas and beyond. Mother Frances Hospital in Tyler was scheduled to open the following day with an elegant ribbon-cutting ceremony. Hospital officials opened its doors early upon learning of the disaster. Bishop Joseph Lynch cancelled the scheduled dedication of the new facility, saying the hospital was already baptized, “in the blood of children.”

Leaders across the country placed their resources at New London’s disposal. Mayor LaGuardia of New York offered manpower and medical supplies, but Texans were already mobilizing necessary aid. Dozens of volunteer embalmers traveled to New London from Dallas and Fort Worth.

Make-shift morgues were set up in nearby churches, stores and other available buildings. The largest morgue was at the skating rink in neighboring Overton. Anguish and shock saturated the air. “Grief was everywhere,” Cronkite later wrote.

Parents looked for their children, first at the hospitals, and then at the morgues. They moved from body to body grimly lifting the sheets. Identification was agonizing. Most victims were unrecognizable.

The severity of disfigurement caused the misidentification of 10-year-olds Wanda Emberling and Dale May York. Dale May’s parents mistakenly buried Wanda as their own, as Arthur and Mildred Emberling made repeated rounds desperately searching for their daughter.

Three days after the explosion, word went out that the sheet-covered remains of one young victim lay unclaimed in Overton. Volunteer Oscar Worrell returned to the morgue and identified his cousin Dale May by a scar on her toe. The body buried as Dale May was exhumed. Just as Worrel had identified his cousin, the Emberlings identified their daughter by her feet. At a party with friends the night before the explosion, Wanda had colored her toenails red with a crayon. The Emberlings recognized her small red toenails in the exhumed casket.

On the day of Wanda’s reburial, the Emberling’s son George succumbed to injuries he received in the blast. Wanda and George are buried side by side in the Pleasant Hill Cemetery with 110 fellow victims of the catastrophe.

Some parents wrapped their children in blankets and drove them to family plots in distant counties and out of state. Many oil field workers moved their families away from New London and never returned.

The blast destroyed enrollment and attendance records. This, combined with the school’s transient demography, makes a precise death toll impossible. However, experts agree the explosion killed close to 300 students and teachers. The good Samaritans who recovered their bodies, proceeded to build the caskets and dig the graves that many of the dead were laid to rest in.

As funerals took place, condolences poured in from around the globe. French students sent money for the victims. Students in Japan sent a telegram expressing their sorrow. Children in Switzerland mailed dozens of handwritten cards. In one of many dark ironies surrounding the devastation, German Chancellor Adolf Hitler wired his sympathy.

Governor Allred wasted no time ordering an investigation. A state military court of inquiry convened in New London just two days after the explosion. Experts from the State of Texas conducted hearings and the governor’s sister-in-law, Lucile Allred, dutifully transcribed them.

Investigators learned that two months earlier, school janitors tapped into the Parade Gasoline Company’s residue gas line. Despite New London’s wealth, the virtue of thrift remained a guiding principle of the school district’s stewards.

As a cost-saving measure, the superintendant cancelled the district’s gas contract. Siphoning off free natural gas, then a waste byproduct of petroleum extraction, was in common practice. The school board members estimated this cost-cutting initiative would save the district $3,000 a year.

Examiners determined the ignition of a large volume of accumulated gas in the building’s subbasement caused the colossal explosion. A spark from the sanding machine in the workshop set off the detonation.

Unknowingly, the janitors left leaks in the gas line fittings. The natural gas leaking into the school was odorless and went undetected. No one thought to associate it with students’ recent reports of headaches and eye irritation.

The court of inquiry concluded the explosion was a terrible accident. No one was found liable. Lawsuits filed by devastated parents were dismissed, but their grievous misfortune resulted in lifesaving laws.

Texas lawmakers mandated the licensure of people installing gas lines. They also enacted legislation requiring the addition of a foul-smelling chemical (mercaptan) to natural gas. This regulation was soon adopted worldwide and has saved countless lives.

Ten days after the nightmare, hundreds of East Texans attended an Easter memorial service in New London. The next day survivors resumed school in the gymnasium and temporary buildings. Four classes of sixth-graders were reduced to one because 87 had been killed.

Awash in shock and grief, New Londoners chose action over paralysis. The school board approved plans for the new school within a week. It opened for fall classes the following year.

Shortly after the new school opened, the New London Baptist Church and New London United Methodist Church moved from the old highway. They rebuilt, like holy citadels, on either side of the school campus.

In 1939, the town erected a cenotaph in the center of Highway 42. The towering granite monument sits atop an empty tomb. The names of known victims are inscribed around its base in memoriam.

The imposing memorial was never dedicated. Grieving parents refused to visit it for decades, their pain too great. The next 40 years, New London’s trauma was marked by silence and protection. New Londoners closed rank and shunned reporters.

“They didn’t trust outsiders with their grief,” according to local historian and museum docent Jimmie Lee Piercy.

During an informal meeting with Lucile Allred in the late 1960’s, when Piercy asked if she could tape record Allred’s recollections of the state hearings, the governor’s sister-in-law pulled out a .38 revolver, laid it on the desk between them and gave a definitive, “No.”

In 1978, survivors of the blast held their first reunion. By then, most of the parents had joined their lost children in death. Survivors embraced, cried, and remembered. Together, they began to heal. Some hadn’t been back to New London since the disaster. Most never spoke of it.

The first reunion was healing and the survivors have since repeated it every two years.

In 1998, the London Museum opened across from the school campus. Museum volunteers are often asked how the people of New London survived a tragedy of such magnitude.

They say strong faith and active churches provided solace. Parents focused on their surviving children. Neighbors checked in on each other. Even Friday night football played an important role, as everyone rallied around the new school.

As Piercy sees it, “This was never a town. It’s a community. We came through because we were unified. We came together. Everyone helped each other. Everyone sacrificed. Even now, we take care of our own. While the museum is a tribute to those we lost, it’s also a testament of the people who survived.”

Sources: Lori Olson, New London School: In Memoriam, March 18, 1937, 3:17 P.M.; R. L Jackson, Living lessons from the New London Explosion; James A.Clark and Michel T Halbouty, The Last Boom: The Exciting Saga of the Discovery of the Greatest Oil Field in America; Lorine Zylks Bright, New London, 1937: The New London school explosion, 1937: One Woman’s Memory of Orange and Green; Walter Cronkite, A Reporter’s Life; David M. Brown and Michael Wereschagin, Gone at 3:17: The Untold Story of the Worst School Disaster in American History; Ron Rozelle, My Boys and Girls Are in There: The 1937 New London School Explosion; “The Day a Generation Died” Documentary Film Produced by Jerry Gumbert; Lawrence W. Speck, former Dean of the School of Architecture at UT Austin; Ron Rozelle, Author; Ellie Goldberg, M.Ed., Director of Healthy Kids; Jimmie Lee Piercy, London Museum docent; and survivor Floy Sutton Metcalf.

New London Explosion Survivor Recalls the Day She Lost Almost All of Her Classmates

I was in the fifth grade, sitting in the back row of Mrs. Hunt’s classroom. We were the only ones who lived — those of us in the back row. My younger brother Max had been in the program in the gymnasium and already gotten on the bus.

I never could remember the explosion. First thing I remember is waking up in the hospital and hearing my mother’s voice. She walked by my bed and didn’t recognize me. My face was so swollen. I couldn’t see, but I cried out for her.

Later she said I looked like a corpse. We all looked alike — living and dead — covered in gray dust. The explosion took my ear off. I was under a doctor’s care in Overton with head injuries for several months.

Each time I asked about a classmate my mother would tell me they had died. I was 11 years old and all of my friends were gone. Max and I cried and begged our parents not to make us return to school in New London. My father worked for Humble Oil and got a transfer.

Much as I’ve tried to forget, every March I go through all of it in my mind again. I’ve been guilty all my life because I was saved and the others weren’t. Almost everyone in my class was killed. Our teacher was killed. Why did I survive? I’ve asked why a thousand times, but there’s no answer. Still, I never stop asking. — Floy Suttle Metcalf, age 91

Last Surviving Rescuer, Marvin Dees, Never Forgets

There were five of us on a crew working in an oil field a few miles south of New London. We heard a terrific explosion but didn’t know what it was. Twenty minutes later someone came by and told us the school blew up. We piled in the company truck and rushed to the scene.

I’ll never forget the sight when we drove up. Horror. I’ve never seen anything so horrible — before or after. It was chaos. Parents were crying and looking for their children. I pitched in with the others and worked all night. We rescued those we could. The rest was digging out bodies and removing the debris. We worked until 10:30 a.m. the next morning.

It’s been 80 years but I remember it like it was yesterday. It flashes through my mind every day.

I try to get up to the (London) museum on Wednesdays. They have a pretty good café there. Wednesday they serve roast beef. I go up there and eat and visit with the people who work there. I need that.

I always try to see if there’s anything good in the terrible things. Far as I’m concerned, the only good thing that came out of the explosion was the odor they added to gas. It makes it easier to detect if there’s a leak. There’s no telling how many people have been saved because of that. — Marvin Dees, age 101

Day of Remembrance

80th Anniversary

March 18, 2017

New London, Texas

The New London community is holding a Day of Remembrance March 18 for the 80th anniversary of the school explosion. Events take place at the West Rusk High School, 10705 South Main Street. Featured guest speaker is State Representative Bryan Hughes. Call the London Museum at 903.895.4602 or visit nlsd.net for more information on the New London school.