By Sarah Melotte, The Daily Yonder

March 21, 2025

Editor’s Note: This post is from our data newsletter, the Rural Index, headed by Sarah Melotte, the Daily Yonder’s data reporter. Subscribe to get a weekly map or graph straight to your inbox.

Earlier this week, the Daily Yonder republished a KFF Health News article about a woman named Barbara Williams with diabetes who lives in rural Alabama. Williams’ hometown of Boligee lacks both high speed internet and enough primary care and behavioral health physicians to treat the community’s residents. She sees a nurse practitioner in a neighboring town to treat her diabetes.

“I know how my sugar affects me,” Williams, who suffers from diabetic neuropathy, told KFF Health news. “I get a headache if it’s too high.”

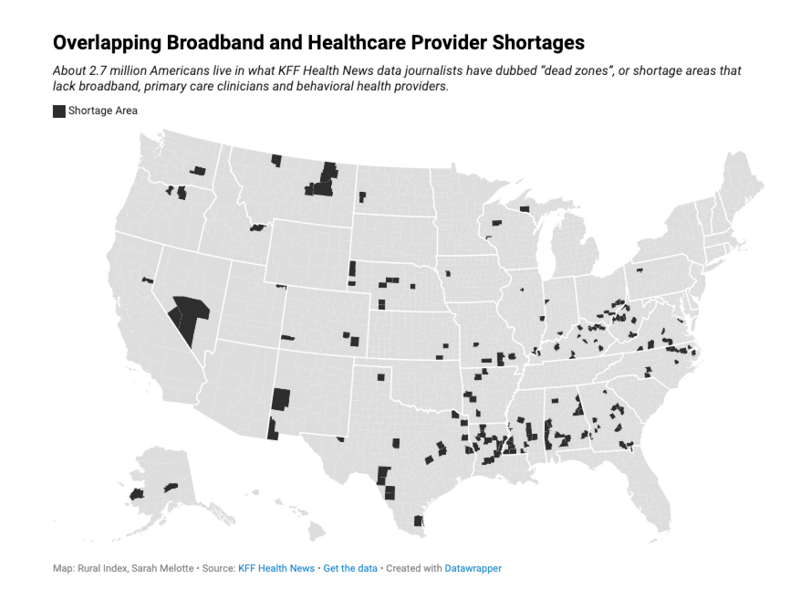

About 2.7 million Americans live in counties where broadband deserts overlap with shortages in primary care providers and behavior health specialists, according to a data analysis from KFF Health News reporters Sarah Jane Tribble and Holly K. Hacker.

KFF Health News journalists refer to these areas as “dead zones.” I will call them shortage areas, in deference to communities there that are very much alive, even though they may not have all the services that most of us can take for granted.

KFF Health News classified counties as shortage areas if fewer than 70% of households had reliable broadband, if the ratio between Medicaid enrollees per primary care provider was in the bottom third of counties, and if the ratio between behavioral health providers per resident was also in the bottom third of counties.

People who live in these counties “live sicker and die earlier,” wrote Tribble and Hacker. Unreliable broadband only widens existing health disparities, like the one between rural and urban residents.

In 2023, the most recent year of available data, 83% of residents in nonmetropolitan, or rural, counties had access to broadband, compared to over 90% of metropolitan residents. And healthcare provider shortages only exacerbate the challenges associated with unreliable broadband, according to KFF Health News.

In a 2022 report, endocrinologist Rashmi Mullur found that patients with diabetes were more likely to be able to control their blood sugar when they had access to telehealth services, for example.

Out of the 2.7 million Americans who live in these shortage areas, almost 2 million, or 70% of them, are from rural counties. That means the rate at which rural residents live in these shortage areas is five times higher than the urban rate.

The rural Black Belt in the American South is a significant hotspot for this phenomenon. The Black Belt refers to a region of historically fertile soil stretching from Louisiana to Virginia. Due to the enduring legacies of racism, slavery, plantation agriculture, and systemic disinvestment, the area remains deeply impoverished. In the map above, the crescent-shaped cluster of counties in the Deep South represents the shortage areas of the Black Belt.

In the Black Belt, 14% of residents live in a broadband and medical-care shortage area, compared to less than 1% of the American population at large. Over 35% of Black Belt residents receive Medicaid, meanwhile.

In rural Holmes County, Mississippi, for example, only 65% of residents have access to broadband internet. About 17,000 residents live in Holmes County, where the median annual income is just over $29,000. Eight-three percent of Holmes County residents are Black or African American, according to Census estimates.

Parts of Central Appalachia are also hotspots for shortage areas.

About 10% of rural West Virginians live in counties where broadband desert and healthcare provider shortages overlap, representing about 187,000 people.

Only 22% of residents in rural Calhoun County, West Virginia, a community of around 6,200 people, have access to broadband. The median income in Calhoun County is about $41,000, about $34,000 lower than the national median.

The work of KFF Health News demonstrates the compounding impact of poverty in rural America. Telehealth offers great promise to deliver care to people who otherwise must go without. But broadband access requires the kind of local investment these same communities are likely not to have. It’s an age-old problem. Those who have less get less.

This article first appeared on The Daily Yonder and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()