By Lisa Tang

As a child in Marshall, Texas, Opal Lee loved the playful joys of an elaborate annual summer community picnic at a local park. The older relatives called it “Juneteenth,” commemorating freedom for enslaved people.

When she was 10 years old, Lee’s family moved to Fort Worth. Just two years later, she learned the harsh realities of racism firsthand as rioters vandalized and set fire to her home.

Born October 7, 1926, to Mattie and Otis Flake, Lee’s childhood memories set the foundation for what became her lifetime mission to advocate for “freedom for everyone.”

In Marshall, with her parents, two brothers, and extended family, the community picnics were happy times with food, competitions, and festivities.

“There’d be music and food; there’d be speeches and food; there’d be games, baseball and food and food and food. Oh, we had a good time, oh we did,” Lee says.

Things got hard on the family during the Depression when Lee’s father lost his job. He departed for Fort Worth to look for work but never sent for his family.

Finding it hard to make ends meet in rural East Texas, Lee’s mother sold everything they had and bought train tickets to Fort Worth for herself and her children. Her parents eventually reunited and bought a house.

Lee hoped for fun summer picnics in their new town, but things were different there than in Marshall.

“When we came to Fort Worth, not so many people celebrated,” she says.

Lee slows the pace of her speech as she tells about her most tragic childhood memory that happened at her family’s home.

“Our house was in a neighborhood where we weren’t wanted,” she says of the mostly Anglo-inhabited area. “On June 19, 1939, about 500 folk gathered — the newspaper said — and the police couldn’t control the mob and while my dad came with a gun the police told him if he ‘busted a cap’ they’d let the mob have us.”

The family escaped with their lives, but the mob destroyed their possessions.

“The people drug furniture out and burned stuff. They really messed the place up. Our parents never, ever discussed it with us and they worked and they bought another home,” Lee says.

Starting over in a different neighborhood, Lee’s struggles continued.

“I finished high school at 16 and my mom was so proud because she was sending me to Wiley College (in Marshall) — and I disappointed her so because I got married,” Lee says. “She was so hurt she didn’t even go to the wedding.”

Unfortunately the marriage didn’t last. Lee had four children to raise when she moved back to her parents’ house in Fort Worth four years later.

With her mother’s help, Lee decided she was ready to attend college. Mattie watched her grandchildren during the week while Lee traveled to Marshall to attend classes at Wiley and work at the college bookstore.

She graduated with a Bachelor of Arts from Wiley in 1953 and taught primary school in Fort Worth for 15 years. Part of that time she also worked at the former Convair — now Lockheed Martin — at night to support her family.

Later, Lee completed a master’s degree in Counseling and Guidance at North Texas State University and served as a counselor who secured social services for struggling families so their kids could attend school regularly.

“I became a visiting teacher to see why the kids weren’t in school,” Lee says.

Those visits opened her eyes to the need to help people with poverty and homelessness after she retired from the school district.

“When I retired, people still needed food and places to stay.”

JUNETEENTH

A seed was planted in young Opal Lee the day the angry mob vandalized her home in 1939. A growing determination took her through raising her children, earning her educational degrees, and eventually finding her place in the world of activism, with a special focus on her beloved Juneteenth celebrations.

“The fact that (the vandalism incident) happened on the 19th day of June spurred me to make people understand that Juneteenth is not just a festival.”

She remembered her grandfather, Zachary Broadous Sr., was the son of an enslaved mother and she learned from him how President Lincoln ended slavery with the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863.

But it was a full two and a half years later when enslaved people of the large, remote, unprotected state of Texas got the news. On June 19, 1865, Major General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston with 2,000 federal troops and served Lincoln’s order to free the enslaved.

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves,” Granger said.

This day of freedom is called Juneteenth, a word combining June and nineteenth. A celebration began in Texas the very first anniversary and continues annually today throughout the country. Descendants of enslaved people who were denied decent foods during servitude, gather to feast on barbecue, strawberry pie, and fresh fruit punch. They honor those who came before and fight for continued rights of equality for Black Americans.

Lee’s activism blossomed after her retirement in 1977. She led Juneteenth celebrations and started a food bank that now serves 500 people a day. In 2019 she started a community farm on 13 acres along the Trinity River. The farm has helped people who were formerly incarcerated and couldn’t find a job.

Lee frequently reads her book about the story of Juneteenth to elementary students.

She wrote a picture book, Juneteenth: A Children’s Story, that she reads to school groups to help educate them on the injustices of slavery. The story is an easy way for children to learn the truth about the darker periods of America’s history. Lee insists that all children need to learn about slavery and the hundreds of years people in bondage waited for freedom.

“I really believe the youngsters need to know what actually happened so we can heal from it,” Lee says. “I go from school to school and read to the children — I get a kick out of it.”

THE HOLIDAY

A number of people over the years, including Lee, believed in order to heal, the importance of a day like Juneteenth deserved national recognition.

Juneteenth was first celebrated in Texas as a state holiday in 1980. In the decades since, the Juneteenth movement gradually gained acceptance as a state holiday across the country. Florida, Oklahoma, and Minnesota were the first three states to recognize it as a state holiday.

Many leaders contributed to the cause. Representative Sheila Jackson Lee (no relation) of Houston introduced a bill for 12 years to recognize Juneteenth as a holiday. Dr. Ronald Myers — who Lee says is responsible for 43 states recognizing Juneteenth as a state holiday — recruited her for the Juneteenth federal holiday campaign.

“Somewhere along the line I got the impression that maybe I needed to do more than what I was doing,” she says.

In 2016 Lee began walking two and a half miles a day from Fort Worth, Texas, to Washington D.C. The 1,400-mile journey was called Opal’s Walk 2 DC.

In 2016, at 90 years old, Lee became committed to bringing awareness of the need for a national day of observance. The idea for Opal’s Walk to D.C. took hold.

“I felt like if a little old lady in tennis shoes [was] walking up and down the highway, people would notice, and they did,” she says.

During Opal’s Walk to D.C. from Fort Worth, Lee walked two and a half miles a day to the capitol to rally support and gather signatures. The length of her daily walks symbolized the two and half years it took for enslaved Texans to learn of their freedom.

One of Lee’s goals was to march with then President Obama when they reached Washington, D.C., in January of 2017, but the president was away in Chicago at another event when they arrived. While that was disappointing, the results of the campaign and continued work with others helped send 1.5 million signatures to Congress in 2020. The group was preparing to submit 500,000 more signatures when Lee received word that she was invited to the White House for a very important occasion.

President Biden signs the bill making Juneteenth a federal holiday as Lee and others look on in 2021.

On June 17, 2021, President Biden signed legislation making Juneteenth a federal holiday.

“Oh, I tell you I’m a happy camper. I’ve not known how to act. I’m still on cloud nine. I thought it would never happen in my lifetime,” Lee says. “I was so happy I was going to do a holy dance.”

The new law ensures federal workers a day off with pay. Lee says that’s important because people can volunteer and uplift others in the community.

“On the Martin Luther King holiday the people don’t say ‘a day off,’” Lee says. “They say ‘a day on’ because they go out in different groups and to different nonprofit organizations, and they help out that day.”

Lee continues to lead Juneteenth celebrations in Fort Worth, which started more than 40 years ago after she helped found the Tarrant County Black Historical & Genealogical Society. Juneteenth celebrations in Fort Worth begin with a flag raising and a prayer breakfast. Youth groups perform a play and a concert known as Empowering You. They also participate in an art competition based on portraying the 12 freedoms Blacks gained when they were released from bondage. These include the ability to read, write, and preserve history; the ability to marry, birth and keep their own children; the right to own property, grow their own food, and dress as they like; the ability to travel, do business, serve in the military, worship, vote, legislate, and govern.

“It’s not just a festival,” Lee says. “And I think we should celebrate it from June 19th to the 4th of July because there’s so much that needs to be taught; there’s so much that needs to be shared.”

After a lifetime of activism, Lee earned the title of “Grandmother of Juneteenth.”

Last year she was named Fort Worth Inc.’s Person of the Year and the Dallas Morning News named her 2021 Texan of the Year.

This year, members of Congress — led by Representative Marc Veasy of Fort Worth — nominated her for a 2022 Nobel Peace Prize. Winners are announced in early October.

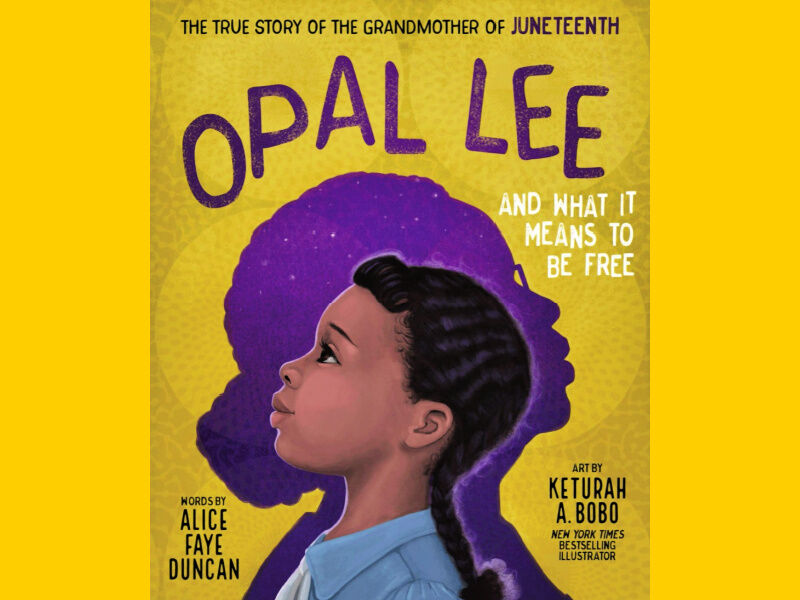

A new children’s book by Alice Faye Duncan premiered in January. Opal Lee and What It Means to Be Free: The True Story of the Grandmother of Juneteenth teaches about Lee’s persistence and determination to gain freedom for everyone.

Lee appreciates the accolades and says she’s not done yet. Bondage is still happening in the forms of joblessness, homelessness, inequities in healthcare and education, sex slavery, and human trafficking, she says.

“There’s still so much that needs to be done before we can say that we’re free,” Lee says. “At 95, I still feel like I have so much to offer. We need to address it. We simply are our brother’s keeper and we ought to do something about these disparities.”

Now that Juneteenth is a federal holiday, Lee wants everyone around the world to embrace it.

“I want to see Juneteenth celebrations all over these United States and around the world,” she says. “It’s not a Black thing and it’s not a Texas thing. It’s for everybody and it’s freedom for everyone.”

Numerous Juneteenth celebrations take place this year across the Upper East Side of Texas. The observed federal holiday is Monday, June 20.

The annual celebration in Lee’s hometown of Marshall holds special meaning this year. Headed by Alma Ravenell, the Marshall Juneteenth Committee is hosting several events June 10-18 under the theme “We Are One.” Activities include a Miss Juneteenth Pageant for 15-19 year old girls, a commemoration program at Wiley College, a parade, a Black business expo, and arts activities at the Michelson Museum of Art.

There’s also a fashion show taking place at Telegraph Park downtown with participants ranging from ages 3 to 83. In one segment, the models wear black and white clothing symbolizing the need to bring people of all skin tones together, Ravenell says.

The Marshall committee doesn’t have anything official planned for the first observed Juneteenth paid federal holiday that Monday, but encourages the community and others to at least get out and go for a walk in memory of Opal Lee and all that the holiday means.

BEST IN THE WORLD

Healing racism is never far from Lee’s heart and she continues to rally others to the cause.

“I’m advocating that everyone should make himself a committee of one because we know people who aren’t on the same page we’re on and we need to change their minds,” Lee says. “Just think, if three million people were on the same page we could turn this country around and make it the country that everyone would want to emulate.”

Simple acts of kindness like helping an elderly person by bringing them food or taking them to the store or helping a young mother with her children while she runs errands are small things people can do.

“All these kinds of things help. It makes us think we are one people,” she says.

Her hope for healing for the country to overcome the injustices of the past and those that continue today is strong. The Grandmother of Juneteenth often thinks about future generations.

“There are people, who if they share the wisdom they have, the young people don’t have to make the mistakes we made,” she says. “Oh gosh, I just see this nation coming together, and I just hope it happens in my lifetime. I do; I do. Let’s get on with the business of making this the best country in the world.”

Early this year, Alice Faye Duncan premiered her book, Opal Lee and What It Means to Be Free: The True Story of the Grandmother of Juneteenth. Through the story of Opal Lee’s determination and persistence, children learn:

• all people are created equal

• the power of bravery and using your voice for change

• the history of Juneteenth, or Freedom Day, and what it means today

• no one is free unless everyone is free

• fighting for a dream is worth the difficulty experienced along the way