By P.A. Geddie

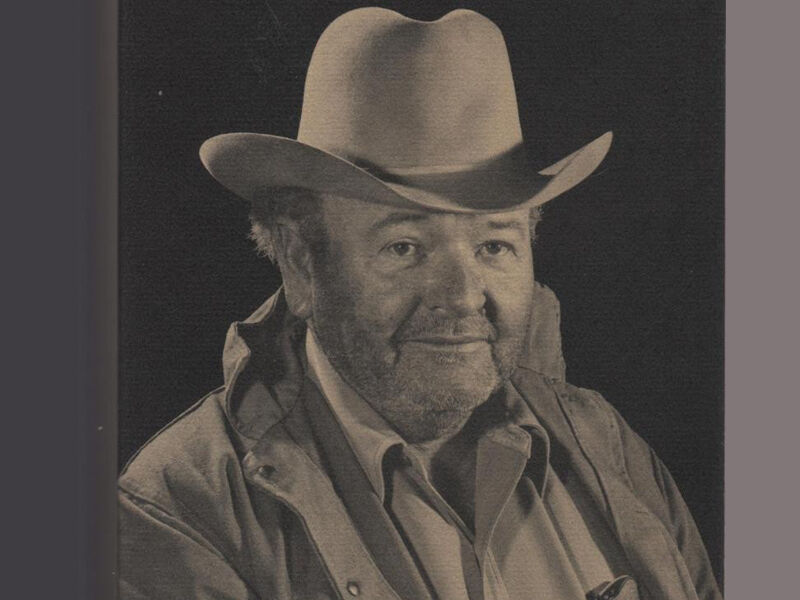

Ben King Green of Cumby, Texas, had a sly cowboy sense of humor and with a golden gift of gab told tales of his days with horses and cattle. Despite his need for an audience from time to time, the call for wide open spaces during his earthly trek ran deep, even into his grave.

In his will, the author and horse doctor donated land to the Cumby Cemetery with the stipulation that he have 100 square feet for himself. He is quoted as saying, “I never let myself be crowded in life, and by God, ain’t nobody gonna close in on me when I’m dead.”

His wishes were honored and his grave stands alone on a grassy knoll with his brand — a G and spurs — engraved in the granite stones standing guard at each corner.

He was born March 5, 1912, to David Hugh and Bird King Green in Cumby, a town his grandfather David W. Cole helped found. He was a firmly rooted Texan with his great-grandparents, B.F. and Lucy Green, becoming citizens of the Republic of Texas upon their arrival from South Carolina. Ben’s grandfather, Miller M. Green, born in 1836 at Daingerfield in Morris County, was a member of the Texas Rangers for two years. Miller helped survey the town of Greenville and served as deputy sheriff when the county seat of Hopkins County was moved from Old Tarrant to Sulphur Springs.

With all that Texan royalty in his veins, Ben learned his place in the world early in life.

“My family had a high standard to raise children by, and as soon as they could tell one wasn’t going to be a credit to the family, they shipped him West, which explains why I left home at such a tender age,” Green said in his book Horse Tradin’, published by Alfred A. Knopf in the 1960s.

Book reviewers often describe Ben as having “crawled out of the cradle and into a saddle” as horses became his whole world during early childhood. He left home on horseback at the age of 12. Although he later moved with his family to Weatherford and attended high school there, he found his best education in wagon yards, mule barns, and livery stables. He learned the art of trading and doctoring horses and by the time he was 16 years old he could make a living at it.

“Cheat or be cheated” was a trading practice he adopted and is reflected in his stories and he didn’t mind stretching the truth now and then.

At one time or another he both claimed and denied that he attended Texas A&M, Cornell University in New York, and the Royal College of Veterinary Medicine in England. The universities have no record of his attending and he did not ever become a certified or licensed doctor of veterinary medicine according to records from the Texas State Board of Veterinary Medical Examiners.

Nevertheless, he eventually became a practicing horse “doctor” along the Pecos and Rio Grande rivers across West Texas and along the Mexico border. He was well respected and his corral-side manner and natural wit earned him the nickname “Doc,” as his extensive experience proved as helpful as formal schooling.

He was in his 50s when he started writing books, a perfect way to tell his tales and stay away from “being crowded” at the same time.

From his book The Village Horse Doctor, West of the Pecos, Green tells tales of his struggles with mean stockmen, yellow weed fever, banditos, poison hay, and “drouth” and covers similar themes in his other books in between horse tales. Those include the previously mentioned Horse Tradin’ followed by Some More Horse Tradin’, and Wild Cow Tales, Horse Tales, The Last Trail Drive, A Thousand Miles of Mustangin’, The Color of Horses, and Horse Conformation.

In an excerpt from Horse Tradin’ published in 1967, Ben talks about his rare times he was out of a horse saddle and into a car.

“I was driving a little six-cylinder, two-toned Buick coupe with a jump seat in the back — which in that time was a sure enough fancy rig for a young man to have for transportation. Of course this fancy automobile was just for special occasions. I didn’t run around town and squeal the wheels on it like I see these flat-top, hot-rod kids doing this day and time. Instead of that, my rig stayed in the barn with a wagon sheet pulled over it until I had some reason to need it. The rest of the time I rode horseback and looked after my cattle, horses, and mules — I did on horseback whatever other business I had to do that didn’t call for a long, fast trip.”

On one such long trip he continues.

“Next morning way before daylight I was up and mounted on this little two-toned, fancy Buick automobile with its spare tires mounted on the sides of the front fenders. It sure was a fancy rig, and I felt like a big operator. I could drive just about as far as the road was cut out in a day, or in a day and night, or from the time I started until the time I stopped. I was young and tough, and sleeping and eating were just something I did on the side when it was convenient and I didn’t have anything else to tend to.”

Ben wrote all of his books the way he operated best. He “talked his books,” he said, telling stories to a tape recorder and to his secretary. He wrote from his own experiences as a rancher, horse and steer trader, wild horse hunter, and horse doctor. He owned the only registered herd of Devon cattle in Texas and supported it on his farm in Cumby, where he also raised Percheron and quarter horses. He was in high demand on the lecture circuit.

In 1973 Ben received the Writer’s Award for contributions to Western Literature from the Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City. He also received a career award from the Texas Institute of Letters for his unique contribution to Texas literature.

He published 11 books between 1967 and 1974. His last, The Color of Horses (1974), was the product of his arduous research through the years on the hide and hair of horses to determine what made color. Ben considered it his most worthwhile contribution, and he saw it come off the presses shortly before he died of heart failure, just a few months after his mother passed away at the age of 94. He died October 5, 1974, at 63 years old, while sitting in his car on a roadside in northwest Kansas, during his last long, fast trip.

The year after he died, the University of Texas Arlington purchased Ben K. Green Papers for their Special Collections Libraries. The collection includes 23 boxes of biographical and family history, correspondence, financial, and legal documents, literary productions, and photographs dated from 1900 through 1976. The photo collection includes friends and family of East Texas near the Green family home in Cumby.

Almost 50 years after his death, the Cumby Cemetery Association continues to ensure no one “closes in on” Ben King Green. His mother and his father, and countless other friends and relatives, are also buried in Cumby Cemetery — just not too close.