By P.A. Geddie

In the 1950s most Americans weren’t familiar with a little country called Vietnam almost 9,000 miles across the Pacific Ocean from Texas. It borders China to the south, appearing on maps as a small slither of land with 2,140 coastal miles along the South China Sea. The whole country is just slightly larger than the state of New Mexico.

France and Japan fought to control it for many years and the North Vietnamese formed their own communist regime.

The Cold War between the communist Soviet Union and the anti-communist United States was under way during those years with both superpowers competing for dominance through psychological warfare, propaganda campaigns, espionage, far-reaching embargoes, rivalry at sports events, and technological competitions such as the Space Race. They also each supported major regional conflicts called proxy wars. The Vietnam War that started as a civil war within South Vietnam became one of them.

By 1956, Vietnam was starting to become more of a household name as American military efforts slowly began to increase in support of South Vietnam while Russia supported North Vietnam. Throughout the 1960s, financial assistance continued to increase as well as military forces and at its peak in 1969, there were 549,000 U.S. troops in Vietnam.

While in World War II, the average infantryman saw 40 days of combat in four years, in Vietnam, the average infantryman saw 240 days of combat in one year.

Through 1975, two and a half million American soldiers got to know Vietnam up close and personal under horrific circumstances. They faced many difficulties and challenges including climate, terrain, a complex political situation, and unclear military objectives.

The average age of the men in combat was 21.

During World War II there was a unified effort where every man, woman, and child contributed in some way to the war effort. It was quite the opposite during the Vietnam War — Americans were not on board. There was a lot of secrecy going on in the American government and leadership did not “rally the home front” for this war. The media received conflicting messages and often reported on the protests and unrest in America with little support for the men in combat. Many Americans opposed the war on moral grounds, appalled by the devastation and violence of the war. Others claimed the conflict was a war against Vietnamese independence or an intervention in a foreign civil war; others opposed it because they felt it lacked clear objectives and was unwinnable.

Winnable or not, American soldiers risked their lives for their country and deserve immeasurable respect. More than 58,000 gave their lives. An estimated 150,000 were permanently physically wounded. They were exposed to Agent Orange and other pesticides that left them battling long-term health issues. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder left many with nightmares to haunt them the rest of their lives. But perhaps the cruelest aspects of the war was the way Vietnam veterans were treated when they came home.

Unlike the return of World War II soldiers who were treated as heroes with parades and street parties, and a whole country celebrating their victories, Vietnam veterans came home to a country of citizens with reactions that ranged from complete apathy to those that took their anger over the war out on the men who served. It was a burden they did not deserve.

Over the next few years, returning Vietnam veterans faced many challenges and found it difficult to find their place in the country they served, then turned their backs on them.

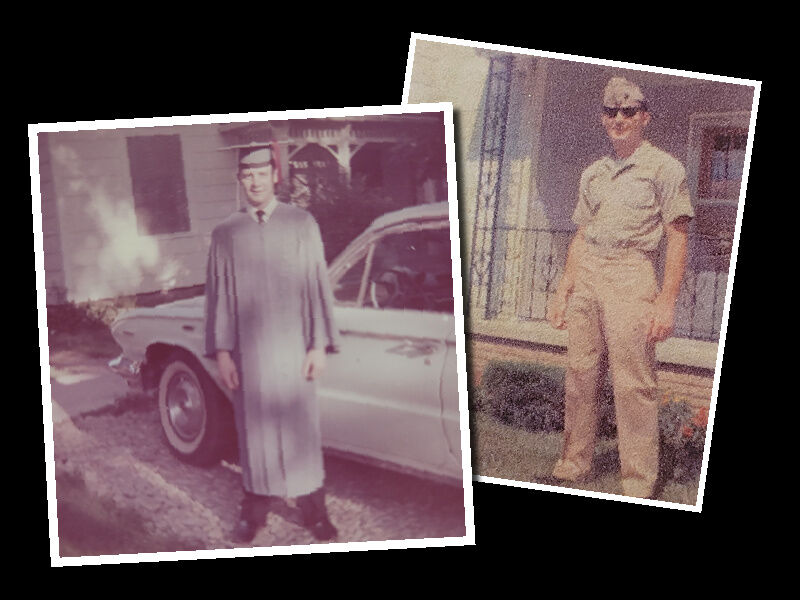

Robert Kerr was just a few years out of high school when he joined the U.S. Marine Corps and soon found himself in the throes of war in Vietnam.

ROBERT KERR

United States Marine Corps

Veteran Robert Kerr lives in Kings Country now, a subdivision on the shores of beautiful Lake Cypress Springs south of Mount Vernon, Texas. It’s a far cry from the rice paddies and war-torn “hell on earth” he left behind in Vietnam 52 years ago.

Born in Lawrence, Kansas, Robert followed in his brother’s footsteps and joined the United States Marine Corps in 1966. Although he didn’t know much about what was going on in Vietnam, he was ready to serve his country.

“I thought I was bullet proof,” Robert says. “I had no fear. I just knew there was a war going on and wanted to do my part. I didn’t have any idea about the politics. I was very patriotic. I was a gung-ho young man. I was a gymnast in high school and at Kansas University and was physically fit. I wanted to show the world what I was worth.”

After training, Robert was not quite 23 years old when he and 219 other soldiers were on an airplane together headed to Vietnam in August 1967.

“I was the oldest and only enlisted man on that plane,” Robert recalls. “The others were all drafted. They dubbed me the ‘old man’ cause all of them were just 18 years old.”

Robert was a trained ammunition technician and was assigned to the northern quadrant in Vietnam. He’d only been there about a month when enemy rockets started hitting the 1,000-acre ammunition depot.

“The Viet Cong rocketed our ammunition sometimes twice a day. One day I happened to be doing inventory in a remote part of the area where there were 500-pound bombs stored in rice paddies. Rockets were falling near me and as I was running a rocket round hit and blew me into a rice paddy. That was the first time I was wounded.”

Robert had shrapnel wounds and couldn’t move for six and a half hours. For quite some time, he was completely deaf.

“I was semi-conscious for hours,” he recalls. “The most traumatic part of that day is when I finally rose up. The rest of the dump was leveled. It looked like the apocalypse.”

He ran three miles to a hospital. Thankfully his injuries were not life threatening.

Robert received letters from home but they didn’t mention much about what was going on in America. Sometimes they’d read the military newspaper Stars & Stripes and get a bit of news that way, but nothing of any great significance.

“We learned how we were winning, taking many casualties, and always on the offensive. I didn’t have any idea of the political things going on. It’s a good thing. That would have been detrimental to our morale. I wouldn’t have wanted to know what was going on and where the politics took it.”

North Vietnamese communist forces began a series of attacks on more than 100 cities and outposts in South Vietnam on January 31, 1968, in an effort to encourage the South Vietnamese to rebel and the U.S. to scale back its involvement in the war. It was called the “Tet Offensive,” named from the Vietnamese New Year holiday during which the attacks occurred. U.S. and South Vietnamese casualties numbered almost 13,000 including almost 3,000 fatalities. Thousands more civilians were killed and wounded.

“I was in the middle of that,” Robert says. “Unlike thousands of former marines who lost their lives, I survived. It was hell on earth.”

Like a lot of soldiers, music of the times helped get him through the horrors of the war.

“CCR was one of my most favorite,” he says, who did songs like “Fortunate Son” and others with links to the Vietnam War. “I love all kinds of music. In Vietnam we heard radio through the BBC so we kept up and knew what was happening in the music industry. The best music in my lifetime happened while I was in Vietnam — ‘60s and ‘70s rock and roll is my favorite.”

Robert served a total of 13 months in Vietnam. On the day he was headed home with other soldiers, they had piled their gear on trucks at the airport and were standing across the way about to board their plane when rockets hit the truck.

“I lost everything I’d gathered during my time there,” Kerr says. “I took nothing with me when I got out of that country.”

Robert said it was quite shocking to him and hurtful to arrive home and feel rejected by his fellow Americans. He was in full uniform when he arrived at the Kansas City airport and first felt it.

“I didn’t feel welcomed. People stared and I had no personal attacks, but I knew that those of us coming back from the war were not well received. I could feel the rejection.”

He tried to make excuses for that believing the American people had been so misinformed.

“I was disenchanted by what had happened and felt really discouraged and hurt by what people had been told and that went on for several years. I wasn’t happy of the U.S. handling of the end of the war in 1975. That didn’t go over well for those of us who had been there.”

Over time, and many years working through Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Robert got involved with veterans organizations and the camaraderie with others helped him heal some.

“I’ve been active in veterans organizations like the VFW and American Legion for a long time. I’ve been involved in Veterans Appreciation programs around East Texas for about eight years.”

He has several social media sites for veterans and is the Judge Advocate for the Marine Corps League 1357 in Sulphur Springs. He’s in several motorcycle groups and says he promotes the military in “every way I possibly can.”

Robert is happily married to his wife Brenda. They have five grown children, 12 grandchildren, and six great grandchildren.

Home was never far from Leonard Jackson’s mind while he served on the front lines as an infantryman for almost a year in Vietnam.

LEONARD JACKSON

United States Army

Leonard Jackson was born and grew up in Mount Vernon, Texas. He was just about 15 years old when he started paying attention to the war in Vietnam. Young men were being drafted right out of high school during those years and he had family that had already been so he knew his time was coming.

“I got drafted in 1969. I was scared out of my boots until I got adjusted, then I was ready to go,” he recalls.

He was 19 years old.

Before he left to serve his country in the army, he married his high school sweetheart, Jackie. Earning weekend passes and other time off to see her helped keep him focused on getting his job done and coming home.

His favorite music helped keep his spirits up too, like The Temptations’ “My Girl,” and “Ain’t No Sunshine When She’s Gone” by Bill Withers. On the night before he left his hometown to go fight a war America demanded he serve, one song in particular got him through: “Only the Strong Survive” by Jerry Butler.

“I played it all night.”

That song would prove to be his mantra. He was trained as an advanced infantry soldier to be part of the military’s main land combat forces in Vietnam.

“Vietnam, here I come,” he said, after his training in California. He fought the Viet Cong for 11 months and 26 days.

He remembers well the conditions of the jungles and the tunnels where he went into daily battle.

“We were ‘tunnel rats’ and had to go in and get the Viet Cong forces that lived underground,” he says. “They had kitchens and cooked in there and slept in there. It’s scary as all get out. It was terrible. Very rough out there.”

Counting dead bodies and looking for those missing in action were regular occurrences, but mostly they were told to keep moving.

“They didn’t want us to see too much of that because it would stay with us. Sometimes you couldn’t help it. It was rough to see your partner laying there.”

These are the memories that move Leonard still.

“I got water in my eyes,” he says. “Over 50 years and still I get teary eyed.”

Mail call was one of the things that helped Leonard keep going. His buddies called him “Little Tex.”

“Every time we got mail, they’d call my name.” He recalls how good that made him feel. “I’d get seven, 12, or 14 letters at a time, tied up in a string.” Jackie wrote often and sometimes he’d get letters from his mother and sister. One time, his sister’s letter simply said, “Congratulations. It’s a boy.” His first son was born while he was still in Vietnam.

Leonard says he relied heavily on prayer during his tour in Vietnam and appreciated when the chaplain came and prayed with the men. He was also grateful for an occasional hot meal.

“Most of the time we had sea rations. We ate out of cans.”

Thanksgiving Day in 1969 is one he’ll never forget as helicopters dropped nets down to them with fresh food.

“I cried like a newborn baby,” Leonard says. “We had green beans, corn, and sliced turkey. It was warm and good.”

He savored every bite and every quiet moment, until later that day, when he was once again in battle with the Viet Cong.

Leonard recalls a couple of times when he ran into guys he knew from back home and how good it was to see them. Always thinking of home is what helped him survive, he says.

Imagine how he felt then, when he arrived back on American soil in his uniform and being called “baby killer” and was spit on.

“It was very ugly,” Jackson says, something he’ll never forget. By the time he got to Love Field in Dallas, he changed into civilian clothes.

“It felt bad. It took some air out of me for a while.”

It was only when he got home to his family, his son now four months old, that he put a barrier up to the meanness of some Americans.

“I made it back to my family. I didn’t care about those other people any more.”

Leonard later lost a leg to diabetes as a result of the Agent Orange he was exposed to in Vietnam.

“That stuff took a toll on my body. A lot of guys got pretty sick on that.”

He worked in factories and a strip mining power plant and then retired a few years ago. He and Jackie have two sons, nine years apart, and are still sweethearts 52 years later. They have two grandchildren that make them proud.

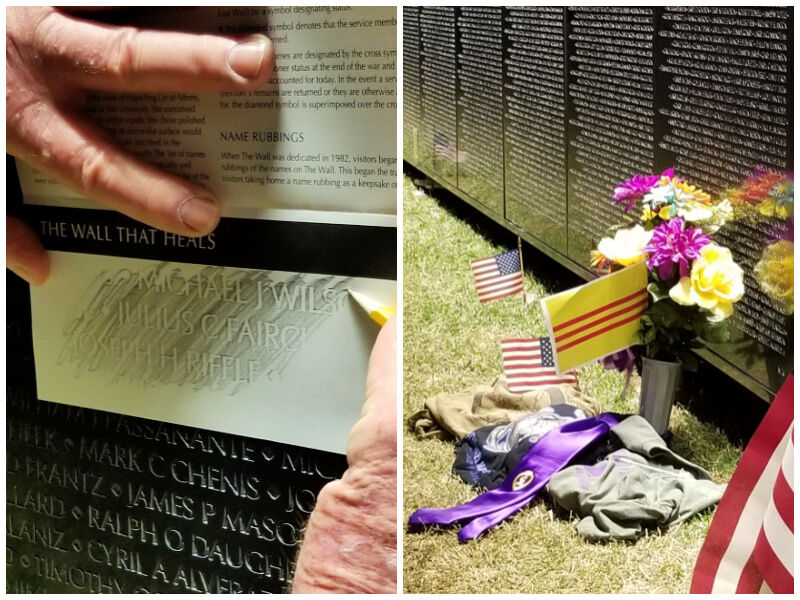

The Wall That Heals is coming to Sulphur Springs November 4-7. It includes the names of more than 58,000 who died or are still missing in action.

THE POWER TO HEAL

In 1977, Jan Scruggs, a Vietnam veteran from rural Maryland, started researching the effects of the war on returning veterans and set out to help them heal. He suggested that the country build a national memorial as a symbol that the country cared about them.

After seeing the movie, The Deer Hunter, about the effects of the war on three friends, their families, and a community, it reminded him of his friends and all the others who died in Vietnam. They all had faces and names, as well as friends and families who loved them dearly. He could still picture the faces of his buddies, but the passing years were making it harder and harder to remember their names.

That bothered him. It seemed unconscionable that he — or anyone else — should be allowed to forget. For weeks, he obsessed about the idea of building a memorial.

“It just resonated,” Scruggs declared one day. “If all of the names could be in one place, these names would have great power — a power to heal. It would have power for individual veterans, but collectively, they would have even greater power to show the enormity of the sacrifices that were made.”

He set out to better define his ideas.

“The memorial had several purposes,” he explained. “It would help veterans heal. Its mere existence would be societal recognition that their sacrifices were honorable rather than dishonorable. Veterans needed this, and so did the nation. Our country needed something symbolic to help heal our wounds.”

While initial attempts to build a memorial were met with skepticism, Scruggs found an ally in former Air Force intelligence officer and attorney Robert Doubek. On April 27, 1979, Doubek incorporated the nonprofit Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund (VVMF) and Scruggs became an officer and director. They recruited other veterans and those that could help them navigate the channels of government authorizations and approvals.

They set their sights in support of the clear, simple vision Scruggs outlined: to honor the warrior and not the war.

In 1980, the United States Congress authorized VVMF to build the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. The organization sought a tangible symbol of recognition from the American people for those who served in the war. By separating the issue of individuals serving in the military during the Vietnam era and U.S. policy carried out there, VVMF began a process of national healing.

Today, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial stands as a symbol of America’s honor and recognition of the men and women who served and sacrificed their lives in the Vietnam War. The two-acre site is dominated by a black granite wall more than 493 feet long. Inscribed are the names of more than 58,000 men and women who gave their lives or remain missing.

The memorial is dedicated to honor the courage, sacrifice and devotion to duty and country of all who answered the call to serve during one of the most divisive wars in U.S. history.

Dedicated on November 13, 1982, the memorial attracts nearly five million visitors each year.

Wanting to reach even more veterans, their families, and others throughout the country, VVMF created a replica of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial designed to travel to communities throughout the United States. Since its dedication on Veterans Day 1996, The Wall That Heals has displayed at nearly 700 communities throughout the nation, spreading the memorial’s healing legacy to millions more.

The Wall That Heals makes only one appearance in Texas this year. On November 4-7, visitors can see the traveling wall and an education center in Sulphur Springs. Find details on www.thewallthatheals-sstx.org or call (903) 243-2206.

Robert Kerr is part of the group that’s bringing it to Texas. This is particularly both exciting and anxiety-ridden for him. He’s tried numerous times in the past to see the traveling memorial and not been able to face it. Once in Missouri, and again in Arkansas, he got to the site and couldn’t get out of the car.

“I had so many lingering memories and I put a lot of things away. I couldn’t bring myself to get out of the car. I didn’t want to bring those memories back and face the things I saw.”

Being heavily involved in bringing the wall to Sulphur Springs, he’s finally going to do it, he says.

“I’m anxious to be involved. I lead the motorcycle escort as it rolls into town and as the wall is being erected, I’ll be leading tours. I’m apprehensive cause I haven’t been able to stand in front of it before. I’m looking forward to it now.”

Robert says he knows it will be difficult seeing all the names. A lot of his friends he lost in the war, their names will be there, even one he grew up with.

“Their names are etched in that wall. It brings it all back. Time has healed my wounds to the point that mentally I can face the facts now that it happened. I don’t have to relive my time in Vietnam. Better to spend time in memory of those that lost their lives there. It’s not about me now, it’s about those that didn’t come home. I’m proud I was there and proud I made it home and I can now memorialize them.”

Although painful to see, Leonard and Jackie Jackson also plan to visit The Wall That Heals to pay their respects to those that did not survive the war in Vietnam.

“I’ll look up some of my friends that didn’t make it back home. It’s a hard pill to swallow. It brings chills,” he says as his eyes once again fill with tears.