By P.A. Geddie

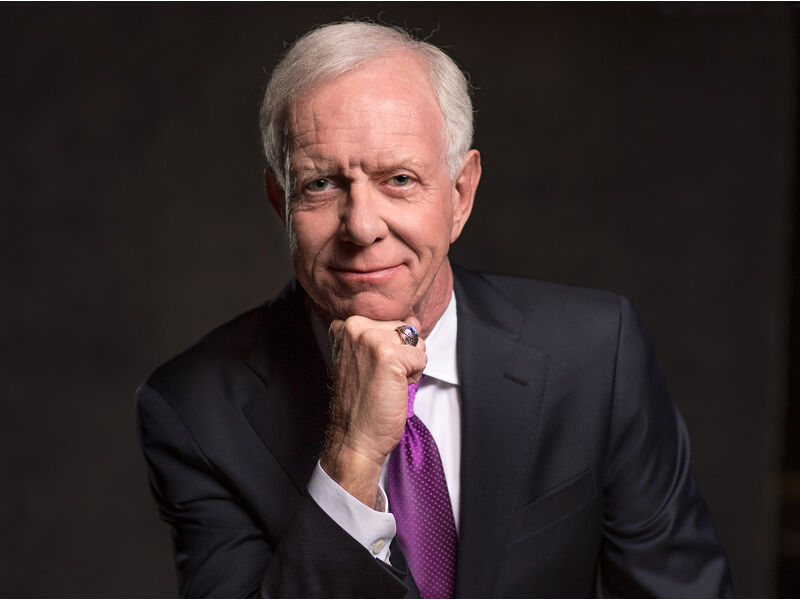

On January 15, 2009, Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger III saved 155 lives when he successfully landed US Airways Flight 1549 in the cold waters of the Hudson River off midtown Manhattan. The event — called the “Miracle on the Hudson” — solidified his status as an international hero and a master in airline safety and effective leadership.

In his memoir, Highest Duty: My Search for What Really Matters, Sullenberger says he realized that his journey to the Hudson River that day didn’t begin at New York’s LaGuardia Airport, but decades before at his childhood Texas home.

“In many ways, all my mentors, heroes, and loved ones — those who taught me and encouraged me and saw the possibilities in me — were with me in the cockpit of Flight 1549. My entire life led me safely to that river,” he says.

ROOTS AND WINGS

Life began for him in Denison, Texas, a town in Grayson County, 75 miles north of Dallas. Born January 23, 1951, he comes from a long line of rural Texans. His parents were born in Denison. His grandparents, from both sides, were from Denison.

The family lived about 10 miles out into the country from town where a combination of rural roots and the importance of education provided a solid foundation for finding his wings.

All four of his grandparents — born in the 19th century — had college educations, something quite uncommon for people during that time, especially women.

“Education has such great value in many ways,” Sullenberger says in a recent County Line interview. “It provides opportunities to live a richer, fuller life.”

His maternal grandmother was an artist who painted portraits for people, as well as still life paintings. She helped her husband with their dairy farm, raising sheep and chickens, and growing alfalfa.

His paternal grandfather passed away before he was born. He’d had a lumber mill in Denison that his grandmother ran after her husband died.

“Nothing like the aroma of freshly-milled wood and big piles of sawdust,” Sullenberger remembers fondly.

His father served in the Navy during World War II and made a living as a dentist. His mother was a first grade school teacher.

“She was a minor celebrity in our town,” he says, because so many remember her as their first teacher.

He has a younger sister, Mary, who graduated from the University of Texas at Austin with a degree in math, became an actuary and was vice president of a large insurance company in Dallas. She, her husband and son live in the Dallas area.

The Sullenbergers lived in a modest home. His father had taken a drafting course in high school and was very enterprising, adding on to the house every few years.

“We each had our own hammer,” Sullenberger says. “We learned by doing — plumbing, roofing, painting, we did it all.”

They also spent time on Lake Texoma, which they could see from their house, and he enjoyed many other aspects of living in the country.

“Being out and seeing the real world through boating, hunting, and fishing — it was a pastoral setting in a time of great optimism when the future seemed boundless,” he says.

He explored the wide-open skies of his childhood often through a small telescope and remembers his father letting him skip school to watch a space launch in the early 1960s.

“It was a time for great exciting dreams to be possible. I never tired of seeing the beauty of the earth or sky, day or night.”

His parents supplied him with a life-long love of reading and coupled with his natural intellectual curiosity, he says he received many wonderful gifts from them that fueled his passion for learning all his life.

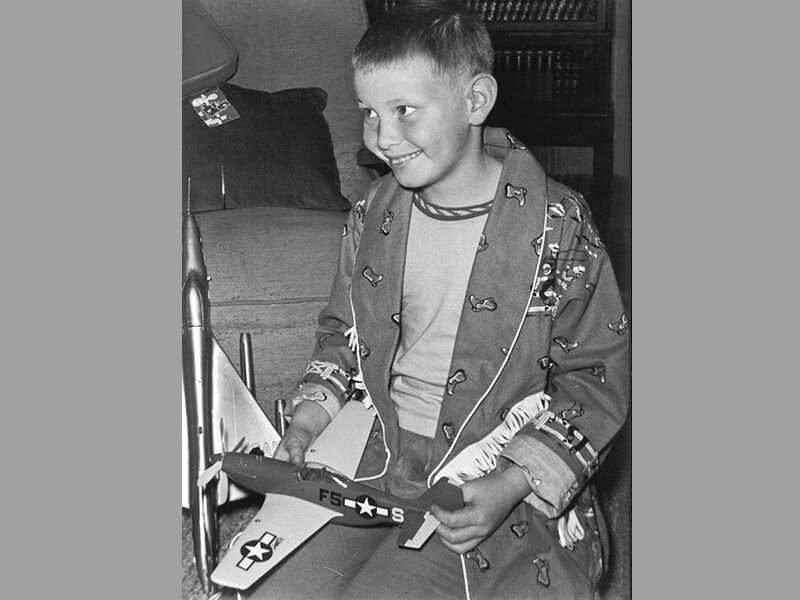

Captain Sullenberger found his life’s passion for flying airplanes when he was very young. He’s about eight years old here receiving a model airplane from his parents on Christmas morning. Photo courtesy of Chesley B. Sullenberger III

“Having a deep and abiding understanding that just ‘good enough,’ isn’t,” he says, “not accepting mediocrity and always trying to improve — that’s what I got from them.”

The family put a lot of power into expectations. “We expect you to do your best, whatever that is. Don’t just get by, but excel,” was a consistent message.

He said the three best things he got from his parents that make him feel fortunate are 1) they created a safe, stable environment; 2) they valued education; and 3) they believed ideas were important.

He devoured copies of Life and Look magazines that his grandparents collected during the war years and his dad’s military books that told stories of men like Winston Churchill and Dwight Eisenhower.

“This idea of genuine leadership — of intense preparation, rising to the occasion, meeting a specific challenge, setting clear objectives — was deeply internalized, burned into and ingrained in my young mind,” he says.

By the time Sullenberger was just five years old he was fascinated by airplanes and flying. They lived near Perrin Air Force Base (it closed in 1971) and he’d watch jet fighters fly over his home.

“It was an active base then and I’d see a daily parade of high-performance jets flying over,” he says. “My dad would give me his binoculars, and I loved looking into the distance, to the horizon, wondering what was out there. It fed my wanderlust.”

Young Sullenberger got his first ride in a plane in 1962, taking a flight out of Love Field in Dallas with his mother when he was 11 years old. He says the airport felt magical to him, filled with larger-than-life people. He noticed the well-dressed travelers with somewhere to go, the flight attendants, and the pilots. As their plane took off he knew that he wanted this life in the air.

Sullenberger as a teenager posing in 1968 with his instructor L.T. Cook who he often credits with giving him the confidence and confirmation that flying airplanes is his calling in life.

He was just 16 when he began taking flight lessons from L.T. Cook, Jr., a former instructor with the Civilian Pilot Training Program and War Training Service before and during World War II. Cook owned a grass airstrip in nearby Sherman and a crop-dusting plane.

Young Sullenberger logged his first flight April 3, 1967, when Cook took him up for 30 minutes.

“I had the controls in my hands from pretty much the first moment,” he recalls.

After 16 lessons over the next couple of months totaling seven hours and 25 minutes, on June 3, Cook told Sullenberger to take off and land three times by himself. He’s never forgotten his first solo flight over the North Texas countryside.

“Climbing to 800 feet above the ground, and then circling the field, I felt an exhilarating freedom. I also felt a certain mastery. After listening, watching, asking questions, and studying hard, I had achieved something. Here I was, alone in the air.

“I can trace my professional experience back to that afternoon,” Sullenberger says. “It was a turning point. Mr. Cook had given me confidence. That first solo flight served as confirmation that this would be my livelihood, and my life.”

By October 1968, he received his private pilot certification. That same month he flew his first passenger, his mother.

During those high school years none of his peers were interested in aviation so he had no one to share that with. If it mattered, he didn’t show it.

“I was an outlier in that way,” he says. “I wasn’t one of the cool kids. I was very focused.”

He mostly kept his attention on academics, although he says he did participate in some athletics.

“I was no star by any means, but I was fit.”

He also loved music, a passion, he says, almost equal to that of flying.

Both he and his sister took piano lessons, but he didn’t stick with it. He played flute in the high school band and sang in his church choir all through high school and later in the Air Force Academy.

“It was a really enjoyable experience for me,” he says, noting that it led to getting to travel and see other parts of the country where they performed.

Sullenberger graduated from Denison High School in 1969 with grades in the 99th percentile and a Mensa (high IQ society) international qualification, as well as his pilot’s license.

One of Captain Sullenberger’s first assignments in the United States Air Force was flying fighters at Luke Air Force Base near Glendale, Arizona. Here he readies for a training flight in 1975. Photos courtesy of Chesley B. Sullenberger III

He was accepted into the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado. He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in psychology and received the Outstanding Cadet in Airmanship Award. He worked his way up through the ranks of fighter pilot, flight leader, and training officer, to captain. For seven more years, he was active duty in North America and Europe and continued his education. He holds masters’ degrees from Purdue University in Industrial Psychology, and from the University of Northern Colorado in Public Administration.

After his military duty, Sullenberger began working for Pacific Southwest Airlines (PSA) (later acquired by US Airways) settling in California. His memoir documents his 30-year career in which he built up an impressive resume, both personally and professionally.

After retiring from US Airways in 2010, Sullenberger continued to pilot privately on short-range business and family trips until the pandemic started in 2020. Photo courtesy of Chesley B. Sullenberger III

In 1986 he met his wife Lorrie who worked in the marketing department at PSA and they married in 1989. They have two daughters, Kate and Kelly.

Their daughters understand the power of expectations and the values Sullenberger learned as a child and are following their own passions.

“There’s a huge advantage to know your passions at a young age,” he says. “We’re fortunate our daughters found theirs at a very early age. So many don’t find that satisfaction until later in life or never quite find it.”

Without any real effort from their parents, the girls focused early on pursuing their own dreams.

“They didn’t need much encouragement,” he says. “They were fairly focused and made their own connection between doing the hard work in order to achieve the outcome.”

Their older daughter Kate is a veterinarian and youngest Kelly is working on her PhD and wants to be a dean of admissions for a college or university.

With education playing such a pivotal role in his upbringing, Sullenberger is proud to have two doctorates in the family. He recalls a time when the girls were much younger — in grade and middle schools — when the topic of college came up at the breakfast table and they were already making plans to go.

“We’re glad you girls want to go to college,” he said to them. “They both looked so shocked and said, ‘You mean we had a choice?’”

Sullenberger said they embraced higher learning wholeheartedly on their own.

“The power of expectations,” he says, remembering those of his own parents. “It’s powerful enough, they got it.”

A couple of years ago, Kelly gave an interview to Pepperdine University Graphic newspaper. It’s clear the lessons her dad learned as a child in the Upper East Side of Texas are continuing through the family tree.

“Being a Sullenberger means living your life with integrity and taking initiative,” Kelly says. “I always joke that those were two of the first words my parents taught me. My dad would always stay afterwards when he would pick me up from preschool, (and) he would make a point, that if the toy room was a mess he would stay and help me pick it up. Just doing the right thing, no matter who is watching and what you get out of it — having really strong values of what is right and wrong have definitely been instilled in me.”

MIRACLE ON THE HUDSON

From what he learned from L.T. Cook on a rural Texas airstrip, to his time with the U.S. Air Force and beyond, Sullenberger rigorously studied other pilots’ mistakes and learned from them. Air safety, leadership, and team building became constant topics in his career.

January 15, 2009, was a normal day, Sullenberger says, as he prepared to take off from LaGuardia airport on US Airways Flight 1549. Just minutes into the flight a flock of Canada geese ran into the airplane and they lost both engines. He called upon everything he knew to form the best plan of action to save all 155 lives on board.

“It was a dire situation, but there were lessons people had instilled in me that served me well,” he says in his memoir. “Mr. Cook’s lessons were a part of what guided me on that five-minute flight. He was the consummate stick-and-rudder man, and that day over New York was certainly a stick-and-rudder day.”

He and his co-pilot, Jeff Skiles, having never met before that week, became fast fellow “soldiers in the trenches,” each knowing instinctively the right things to do in the few minutes they had to make good decisions. Getting back to the LaGuardia airport, or Teterboro ahead of them, was determined too risky. If they didn’t make it, not only would they take the lives of all on board, but many people on the ground in this densely populated area.

When Sullenberger made the decision that their best option was to land on the icy Hudson River, he had many things to consider. He was confident about being able to land safely there but knew that the plane would not float for long.

“In my mind I thought it might float a half hour,” he says, which is what happened.

The water temperature was 38 degrees and air temperature was 20 so people could not long stand the water. He knew he had to land where they would be seen and rescued quickly. So he carefully and thoughtfully landed near the ferry boat terminal.

The ferry boats came quickly. All 150 passengers and five crew members were rescued.

“Our performance — mine, Jeff Skiles, the crew — we weren’t perfect. But we found a way to do something that worked. It was a challenge we never anticipated. We never trained for this. I knew intuitively to choose to do a handful of important things and do them extremely well. It was no time for multitasking, but for great mental discipline.”

One of the things that calmed him during the frightening few minutes of the landing, he says, is hearing the flight attendants taking charge with the passengers, and that the passengers for the most part, seemed to follow their directions. After he announced, “This is the captain. Brace for impact,” he heard the attendants shouting their commands, “Brace, brace, brace. Heads down. Stay down.”

Knowing his team was on the same page encouraged him to think they could rescue everyone.

“Their direction and professionalism would be keys to our survival, and I had faith in them.”

(Hear Captain Sullenberger explain exactly what happened when he successfully landed US Airways Flight 1549 on the Hudson River in this VIDEO)

(See the 10 year reunion of the crew and passenger in this coverage with Amy Robach, ABC News.)

WHAT REALLY MATTERS

Sullenberger was two years and eight days shy of 60 years old when he performed the miracle on the Hudson.

“Experience matters,” Sullenberger says. “It literally makes the difference between success and failure, life and death.”

He often gives credit to his first flight instructor L.T. Cook where his experiences began and thought of him often after the landing, he says. Cook died in 2001 at the age of 88. After the heroic landing of Flight 1549, Sullenberger received thousands of emails and letters from people all over the world. Among them was one from Cook’s widow, Evelyn.

“L.T. wouldn’t be surprised,” she wrote, “but he certainly would be pleased and proud.”

Sullenberger returned to his hometown of Denison in June 2009 just five months after the emergency landing. He was invited to help pay tribute to military veterans on the 65th anniversary of the Normandy invasion of World War II, and the other hometown hero, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, born there in 1890. A parade and other accolades welcomed Sullenberger and he addressed the 2009 graduating class at Denison High School, 40 years after his own graduation there. He was also able to see and thank Evelyn Cook. Soaking in all the memories and warm wishes, he addressed the crowd after the parade and asked, “How come you weren’t this nice to me back in high school?”

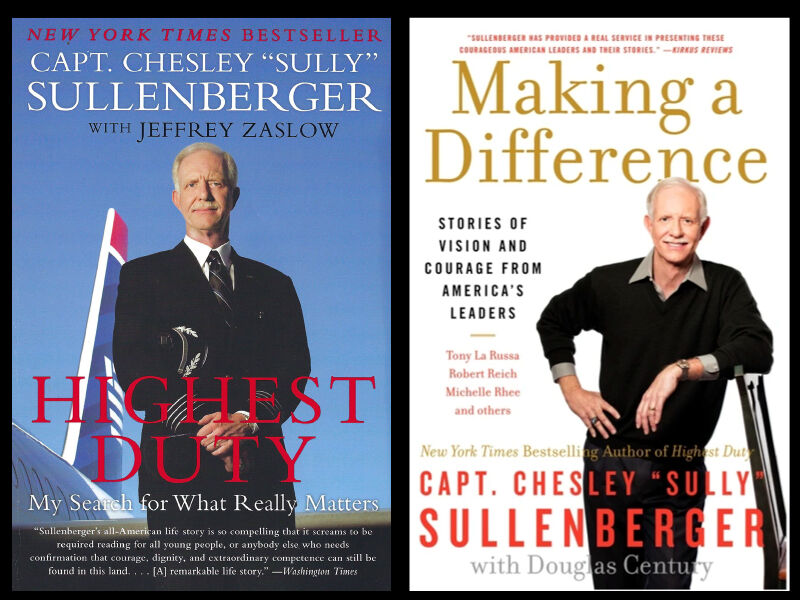

Sullenberger’s memoir Highest Duty: My Search for What Really Matters released in October of 2009. It is cowritten by Jeffrey Zaslow.

In it, he gives an in-depth view to his childhood, military service, career as a commercial pilot, his wife and daughters, the intense landing on the Hudson River, and his commitment to excellent leadership.

His interest in highlighting true leadership led him to write another book in 2012 with Douglas Century. In Making a Difference: Stories of Vision and Courage from America’s Leaders, he engages some of the most accomplished men and women in the fields of technology, medicine, education, sports, philanthropy, finance, law, and the military in inspiring conversations.

Through his books, speaking engagements, and consultations, he shares management principles of “leadership by personal example” and the lessons from his life that prepared him to handle the landing on the Hudson.

His input on the safety of the flying public is sought from all over the world. Recently he appeared on an episode of 20/20 as part of a thorough investigation into two Boeing 737 Max airplanes that crashed and killed 346 people.

Although Sullenberger says he’s no hero, he knows the safe landing on the Hudson is important. He’s proud to use his prominence to drive home the message that people — no matter their station in life — can make a difference.

“There’s a big difference between being famous and being someone who has real core values and lives them on a daily basis,” he says. “People all the time are doing valuable things, heroic things. We don’t always hear about it but that doesn’t make it less valuable. Pharmacists, bus drivers, public officials, airline pilots — we depend on them to have the integrity to do the right thing at the right time for the right reasons.

“We need to try to do the right thing every time, to perform at our best, because we never know which moment in our lives we’ll be judged on.”

Nearly 12 years after writing Highest Duty, “what really matters” remains the same.

“It’s what we do for each other,” he says. “There are rights and responsibilities of citizenship. It’s not the winner-take-all world that some who are motivated by their self interests believe. There are things we owe to each other. Civilization isn’t possible without it. My ultimate message is we’re all in this together.”

To buy Sullenberger’s books and learn more about his speaking topics, visit www.sullysullenberger.com.